1688: The Arrival of the French Huguenots

Persecution in France and the VOC's Recruitment Policy

In October 1685, King Louis XIV of France revoked the Edict of Nantes, originally issued by Henry IV in 1598 to grant religious tolerance to Protestants. This Fontainebleau Edict unleashed severe persecution on the Huguenots—French Calvinists who comprised a skilled middle class of artisans, farmers, merchants, and professionals. Dragonnades saw soldiers billeted in Protestant homes to force conversions, while galleys, imprisonment, and execution awaited the defiant. Thousands fled illegally, often at great risk, losing property and facing death if caught. An estimated 200,000 to 300,000 Huguenots escaped to Protestant refuges like the Dutch Republic, England, Germany, Switzerland, and later North America. In the Netherlands, many integrated into the prosperous Dutch society, bringing expertise especially in viticulture from regions like Champagne, Bordeaux, and Languedoc. The Dutch East India Company (VOC), aware of persistent agricultural shortcomings at the Cape Colony—where early attempts at large-scale farming and wine production had yielded poor results despite Jan van Riebeeck's efforts—saw these refugees as ideal settlers. From 1685 onward, the VOC's directors in Amsterdam and the Cape's governors actively encouraged Huguenot migration, offering free passage on return fleet ships, land grants equivalent to those of free burghers, tools, seeds, and exemption from certain taxes for years. This was not mere charity but a calculated policy to bolster the colony's population with diligent, skilled Protestants who shared the Reformed faith, addressing the slow growth of the European settler base that had reached only about 600 free burghers by the mid-1680s, hampered by high mortality, returns to Europe, and reliance on company employees.

Governor Simon van der Stel and the Strategic Settlement

Simon van der Stel, governor of the Cape from 1679 to 1699, played a pivotal role in welcoming and integrating the Huguenots. Himself of mixed Dutch and Asian-Indian descent, van der Stel was a capable administrator who founded Stellenbosch in 1679 and expanded the colony's boundaries. He personally selected fertile lands for the newcomers in the berg river valley regions, deliberately distancing them from Cape Town to create concentrated farming communities while avoiding the formation of a separate French enclave that might resist assimilation. Prime areas included Drakenstein (later Paarl), the valley soon called Franschhoek ("French Corner" due to the high concentration of Huguenots), Wagenmakersvallei (Wellington), and extensions around Stellenbosch. Farms were granted on the freehold system, typically 60 morgens (about 51 hectares) each, with many named after French origins—La Motte, Provence, Languedoc, La Rochelle, Cabrière—reflecting nostalgia for home. Van der Stel ensured that Huguenot plots were interspersed with Dutch ones to promote intermarriage and cultural blending, a policy that proved remarkably effective. The governor also provided initial support with tools, seeds, and livestock to help the newcomers establish their farms quickly and contribute to the colony's growth.

The Journey, Arrivals, and Key Families

The migration unfolded gradually rather than in one wave. The first Huguenots trickled in from 1685, but the main influx occurred between 1688 and 1700. On 13 April 1688, the largest single group—around 38 adults and children—arrived aboard ships like the Voorschoten, Borssenburg, and Oosterlandt. Further parties followed on vessels such as the Berg China (1688), Zuid-Beveland (1689), and Driebergen (1698). In total, approximately 180 to 200 individuals settled, a modest number that nonetheless represented nearly one-sixth of the free burgher population at the time. Many came from northern France (Picardy, Normandy) and the west (La Rochelle area), with notable families including de Villiers (from La Rochelle), du Toit, Joubert, le Roux (often from Normandy), Malan, Marais, Nourtier, Pinard, Retief (whose descendant Piet Retief would lead a Great Trek party), Theron, and du Plessis. These families brought not only farming skills but also crafts like wagon-making, barrel cooperage, and silk production attempts. Initially, they maintained French-language church services under ministers like Pierre Simond, who arrived in 1688 and served until returning to Europe in 1702.

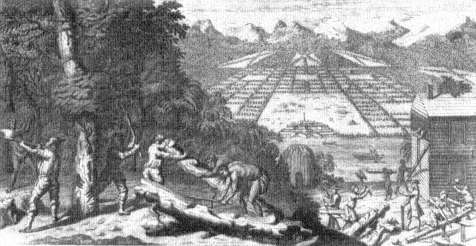

Transformative Contributions to Agriculture and Viticulture

The Huguenots' most enduring impact was on Cape agriculture, particularly viticulture. Early Dutch attempts at wine-making, starting with van Riebeeck's 1659 first pressing, had produced mediocre, short-lived wines due to unsuitable varieties and techniques. The Huguenots, drawing on expertise from France's premier wine regions, introduced superior grape varieties like Semillon (known locally as Green Grape), Chenin Blanc, and Muscat, along with better pruning, trellising, and fermentation methods. Estates like Boschendal, La Motte, and Cabrière quickly gained reputation for quality wines, with production surging—by 1700, the Cape exported wine to Europe, and Constantia wine (though initiated earlier) benefited from their refinements. General farming also advanced: improved wheat yields, fruit orchards, and livestock breeding contributed to greater food security for the refreshment station and growing settler needs. Their strong work ethic, rooted in Calvinist values of diligence and frugality, set a cultural tone that influenced the emerging frontier society. Their technical innovations laid foundations for the Cape's later renowned wine industry, still evident today in the Winelands.

Rapid Assimilation and the Enduring Boer Legacy

Despite initial cultural distinctiveness—French names, language in homes and early church records—the Huguenots assimilated swiftly into the Cape's European community. Shared Calvinist religion facilitated unity with Dutch settlers, while VOC policies accelerated the process: from 1701, Dutch became mandatory in schools and official church services, and intermarriage was common from the first generation. By the mid-18th century, French as a community language had vanished, absorbed into the evolving Cape Dutch dialect that would develop into Afrikaans. Yet the genetic and cultural imprint was profound—though only 15-20% of the settler population by 1700, Huguenot descendants contributed an estimated 20-30% to later Afrikaner/Boer ancestry due to higher birth rates and inward marriage patterns. Surnames like de Villiers, du Toit, Joubert, le Roux, Malan, and Retief remain common among Afrikaners, and their emphasis on education, family, and resilience shaped frontier values. This French infusion enriched the primarily Dutch-German base, helping forge a hardy, adaptive people suited to Africa's challenges—the Boers—who would expand inland as trekboers in the 18th century, carrying blended traditions forward.

.

References / Disclaimer