1688: The Persecution and Arrival of the French Huguenots

French Huguenot Persecution in France

The persecution of the French Huguenots, Protestant followers of John Calvin's Reformed teachings, represents one of the most intense episodes of religious intolerance in early modern European history. Originating in the mid-16th century amid the French Wars of Religion (1562–1598), Huguenots faced intermittent violence and discrimination despite comprising a significant minority—estimated at 7–10% of France's population by the late 16th century, concentrated in urban areas and southern regions like Languedoc, Dauphiné, and Provence. Many were skilled artisans, merchants, farmers, and professionals, forming a prosperous middle class that contributed disproportionately to France's economy.

The turning point came with the Edict of Nantes, signed by King Henry IV on April 13, 1598. A former Huguenot who converted to Catholicism to secure the throne, Henry issued this edict to end decades of civil war that had devastated the kingdom. It granted Huguenots substantial rights: freedom of worship in designated areas, access to public office, civil equality, and military strongholds for protection. While upholding Catholicism as the state religion, the edict promoted civil unity and was registered as a "fundamental and irrevocable law." Supplementary brevets provided subsidies for Protestant pastors and garrisons. For nearly a century, it ensured relative peace, though Catholic clergy and hardliners never fully accepted it, viewing Protestantism as heresy.

Under Louis XIII (r. 1610–1643) and his minister Cardinal Richelieu, pressures mounted. The Peace of Alès in 1629, following Huguenot rebellions, stripped Protestants of military and political privileges while retaining religious freedoms. Churches were demolished in some areas, and conversions were encouraged through incentives. Louis XIV (r. 1643–1715), the "Sun King," inherited a centralized absolutist monarchy and sought complete religious uniformity to bolster royal authority. Influenced by devout Catholic advisors and his confessor Père La Chaise, he viewed the Huguenots' existence as a challenge to "one king, one law, one faith."

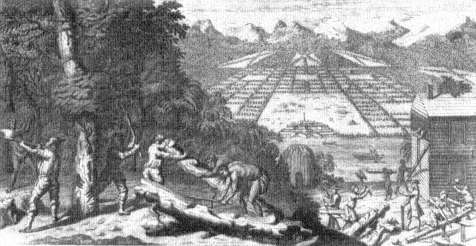

Persecution escalated gradually. From the 1660s, legal restrictions eroded the Edict: Protestant schools and hospitals closed, mixed marriages invalidated, and children from age seven could abjure Protestantism and be removed from parents. Catholic conversions to Protestantism were banned, and Huguenot access to professions limited. By 1681, Louis XIV intensified efforts with the infamous dragonnades. Coined from the dragoons (mounted infantry) involved, this policy quartered unruly soldiers in Huguenot homes, granting them license to loot, destroy property, and terrorize families. Starting in Poitou under intendant René de Marillac, it spread to regions like Béarn, Languedoc, and Dauphiné. Soldiers were billeted indefinitely until conversion certificates were produced, often involving violence, rape, and torture. Whole towns converted en masse to avoid ruin; estimates suggest 300,000–400,000 abjured under duress, receiving financial rewards and tax exemptions.

Despite these "successes," resistance persisted. Louis XIV, informed that Protestantism was nearly eradicated, revoked the Edict of Nantes with the Edict of Fontainebleau on October 18, 1685, signed at his palace. This declared the edict redundant due to mass conversions and outlawed Protestantism entirely. Key provisions included: destruction of remaining Huguenot temples (churches), closure of schools, exile of pastors within 15 days (unless they converted), prohibition of private worship, mandatory Catholic education for children, and a ban on emigration for lay Huguenots—punishable by galley slavery or death. Pastors converting received pensions; defiant ones faced execution.

The revocation triggered a mass exodus, known as the Refuge. Despite border guards and severe penalties, 200,000–300,000 Huguenots fled illegally over decades, often via perilous mountain passes or sea routes. They lost property (confiscated or sold cheaply) and risked capture. Destinations included the Dutch Republic, England, Brandenburg-Prussia, Switzerland, Geneva, and even North America and the Cape Colony. France suffered a "brain drain": skilled workers in silk weaving, clockmaking, glassmaking, and viticulture emigrated, boosting competitors' economies—e.g., Prussian silk industry or English manufacturing.

The persecution's legacy was profound: it weakened France economically and demographically while dispersing Huguenot expertise across Protestant Europe. Only in 1787, with the Edict of Versailles under Louis XVI, were limited rights restored, paving the way for full emancipation during the French Revolution. The dragonnades and revocation remain symbols of state-sponsored religious terror, highlighting the dangers of absolutism and intolerance.

Arrival,Contributions to Agriculture and Viticulture

The first French Huguenot to settle at the Cape was François Villion (later Viljoen), a wagon-maker who arrived individually in 1671. Organized group migration began much later, following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) actively recruited skilled Protestant refugees, and the main influx occurred between 1688 and 1700, with around 180–200 Huguenots arriving in total.

The largest single group landed on 13 April 1688 aboard ships including the Voorschoten, Borssenburg, and Oosterland, carrying families from wine-growing regions such as Provence, Champagne, Languedoc, and the Loire. Further arrivals followed on vessels like the Berg China (August 1688) and Zuid-Beveland (August 1689), which brought the first French pastor, Pierre Simond.

Upon arrival, Governor Simon van der Stel allocated fertile land in the Berg River Valley to promote rapid agricultural development and assimilation. Farms of approximately 60 morgen (about 51 hectares) were granted on freehold basis in areas that became known as Drakenstein (Paarl), Franschhoek (“French Corner”), Stellenbosch, and Wagenmakersvallei (Wellington). To encourage integration, Huguenot plots were interspersed among those of Dutch settlers, and many farms were named after French places of origin—Champagne, Bourgogne, Provence, La Rochelle, and Cabrière.

Their farming contributions were immediate and far-reaching. Drawing on expertise from France’s premier wine regions, the Huguenots dramatically improved viticulture, which had previously produced only poor-quality wine under Dutch efforts since Jan van Riebeeck’s initial plantings in 1655. They introduced superior grape varieties (notably Chenin Blanc/Steen and Semillon/Green Grape) and advanced techniques in pruning, trellising, soil management, and fermentation. Vine numbers soared from a few hundred to over 1.5 million by 1700, enabling the production of export-quality wines.

Prominent Huguenot-founded estates include La Motte, Haute Cabrière, Boschendal, La Bri, L’Ormarins, and Picardie—many still bearing French names today. Beyond viticulture, they boosted wheat yields, expanded fruit orchards, improved livestock breeding, and developed essential crafts such as cooperage and wagon-making. Their diligence and specialised knowledge transformed the Cape from a struggling refreshment station into a productive agricultural colony and laid the enduring foundations for South Africa’s world-class wine industry.

Rapid Assimilation and the Enduring Boer Legacy

Despite initial cultural distinctiveness—French names, language in homes and early church records—the Huguenots assimilated swiftly into the Cape's European community. Shared Calvinist religion facilitated unity with Dutch settlers, while VOC policies accelerated the process: from 1701, Dutch became mandatory in schools and official church services, and intermarriage was common from the first generation. By the mid-18th century, French as a community language had vanished, absorbed into the evolving Cape Dutch dialect that would develop into Afrikaans. Yet the genetic and cultural imprint was profound—though only 15-20% of the settler population by 1700, Huguenot descendants contributed an estimated 20-30% to later Afrikaner/Boer ancestry due to higher birth rates and inward marriage patterns. Surnames like de Villiers, du Toit, Joubert, le Roux, Malan, and Retief remain common among Afrikaners, and their emphasis on education, family, and resilience shaped frontier values. This French infusion enriched the primarily Dutch-German base, helping forge a hardy, adaptive people suited to Africa's challenges—the Boers—who would expand inland as trekboers in the 18th century, carrying blended traditions forward.

.

References | Disclaimer

Boer History

Boer History