The Establishment of the Cape Settlement in 1652

The Dutch East India Company and the Need for a Cape Station

The foundation of the Dutch settlement at the Cape of Good Hope can be traced to the initiatives of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), formed in 1602 as a chartered enterprise with monopoly rights over trade routes to Asia. This organisation, governed by the Heeren XVII—a board of seventeen directors representing the major Dutch chambers of commerce—sought to secure its maritime operations against rivals such as the Portuguese and English. The Cape's strategic position midway on the voyage from Europe to the East Indies made it essential for resupply, as ships faced prolonged journeys of up to nine months, during which scurvy and other ailments from inadequate provisions led to high mortality rates among crews.

Jan van Riebeeck's Background and Early Career

Jan van Riebeeck, appointed commander of the new station, was born on 21 April 1619 in Culemborg, a town in the province of Gelderland in the Netherlands. His father, Anthony Jansz van Riebeeck, was a surgeon who died when Jan was young, leaving the family in modest circumstances. Van Riebeeck received a basic education and, lacking substantial inheritance, entered the VOC's service in 1639 at the age of twenty, initially as an assistant surgeon, a common entry point for those with medical knowledge in an era when surgical skills were valued for treating wounds and illnesses aboard ships.

Van Riebeeck's early career with the VOC involved postings across Asia, reflecting the company's expansive network that included factories in India, Persia, and the Spice Islands. He arrived in Batavia, the VOC's administrative centre in Java (modern Jakarta), which served as a depot for spices like nutmeg, cloves, and pepper, as well as silks and porcelains from China. In 1643, he was assigned to the trading post at Dejima, an artificial island off Nagasaki in Japan, where the Dutch held exclusive European trading privileges following the expulsion of the Portuguese. There, the VOC exchanged European goods, including woollens and metals, for Japanese silver, copper, and lacquerware. By 1645, van Riebeeck had risen to head the station at Tonkin in northern Vietnam, a key source of silk and ceramics, but his tenure ended abruptly when he was caught engaging in private trade, a violation of VOC regulations designed to prevent employees from undercutting company profits. Such practices were widespread due to low official salaries, but van Riebeeck's detection resulted in dismissal, a fine equivalent to several months' pay, and forced repatriation to the Netherlands in 1648.

Van Riebeeck's Proposal and the Decision to Establish the Station

En route back to Europe in 1647, van Riebeeck's ship, part of a homeward-bound fleet, anchored at Table Bay for eighteen days to repair damage from storms. This stopover allowed him to observe the Cape's natural advantages: a sheltered bay protected by Table Mountain, abundant fresh water from streams fed by mountain runoff, and a mild Mediterranean climate with wet winters and dry summers conducive to agriculture. He noted the presence of wild game, fish, and edible plants, and the potential for trading with local inhabitants for cattle and sheep. Upon returning to the Netherlands, van Riebeeck submitted a memorandum to the Heeren XVII advocating the establishment of a permanent station to provide fresh produce, meat, and water, thereby reducing losses from disease on the long voyages. His proposal aligned with earlier ideas from company officials, but it gained urgency after the wreck of the VOC vessel Haerlem in March 1647 near Table Bay. The sixty survivors, led by merchant Leendert Jansz, built a makeshift camp called Fort Sandenburgh and sustained themselves for five months by gardening, hunting, and bartering with indigenous people, proving the site's feasibility. Jansz and surgeon Mathys Proot returned to the Netherlands in 1648 with positive reports, prompting the Heeren XVII to approve the plan in 1649.

The Expedition and Arrival in Table Bay

Preparations for the expedition began in 1651, with van Riebeeck selected as commander due to his experience and the memorandum's influence. On 24 December 1651, he departed from Texel aboard the Drommedaris, a 35-metre fluyt ship capable of carrying 200 tons of cargo, accompanied by the Reijger, a smaller vessel, and the Goede Hoop, a pinnace for coastal navigation. His wife, Maria de la Queillerie, a French Huguenot from a family of Protestant refugees, and their infant son Abraham joined him, along with a contingent of about ninety people, including eighty-two men—soldiers, sailors, craftsmen, and farmers—and eight women, mostly family members. Two additional ships, the Walvis and Oliphant, followed in early 1652 but were delayed by North Sea gales that caused structural damage and the loss of over 130 lives from exposure and shipboard accidents. The fleet endured a four-month voyage marked by equatorial heat, calms in the doldrums, and southern storms, arriving in Table Bay on 6 April 1652. This marked the start of a permanent VOC presence, intended solely as a refreshment post rather than a colony, to support the company's annual traffic of dozens of ships transporting spices, textiles, and personnel between Europe and Asia.

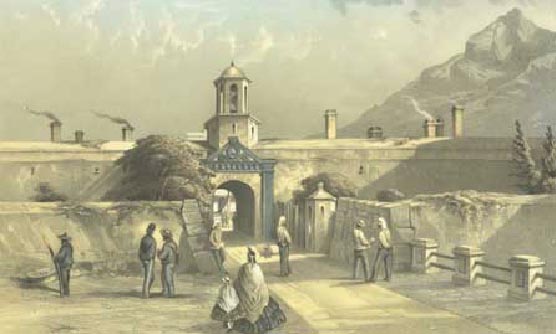

Construction of the Fort de Goede Hoop

The VOC's instructions to van Riebeeck emphasised efficiency and cost control: establish a fort for defence against potential attacks from European rivals or locals, cultivate gardens for anti-scorbutic fruits and vegetables, and secure livestock through trade without provoking conflict. Construction commenced on 7 April 1652, as documented in van Riebeeck's detailed journal, which served as an official record for the Heeren XVII. The Fort de Goede Hoop was designed as a square earthwork, approximately 32 metres on each side, with ramparts of compacted clay, sod, and timber reinforcements sourced from local forests on Table Mountain's slopes. At each corner stood a pointed bastion for mounting cannon, providing overlapping fields of fire in the style of contemporary Dutch fortifications influenced by engineers like Simon Stevin. The bastions were named after four of the expedition's ships: Drommedaris, Reijger, Walvis, and Oliphant, symbolising the maritime origins of the venture. Inside the fort were basic structures including barracks for the garrison, a thatched council chamber doubling as a chapel, storerooms for provisions and trade goods, a hospital ward, and workshops for carpentry and blacksmithing. Positioned near the freshwater stream now underlying Adderley Street in modern Cape Town, the fort was completed in rudimentary form by mid-1652 and fully operational by 1653, though constant repairs were needed due to erosion from winter rains.

Agricultural Efforts and Initial Challenges

Agricultural efforts began concurrently, with plots cleared along the Liesbeeck and Varsche rivers and on the lower slopes of Table Mountain, where the fertile volcanic soil, enriched by decomposed basalt, promised good yields. Seeds brought from the Netherlands and Batavia included cereals such as wheat, barley, oats, and rye for bread-making; vegetables like cabbages, carrots, onions, and pumpkins for sustenance; and fruit trees including apples, pears, oranges, lemons, and vines to produce citrus and wine as scurvy preventatives. Livestock imported on the ships—cattle, sheep, pigs, and poultry—were housed in enclosures, but initial attempts at farming faced severe setbacks during the first winter from May to August 1652, when torrential southeast winds and floods washed away plantings, drowned animals, and turned fields to mud. Diseases such as dysentery and respiratory infections, exacerbated by damp conditions and poor sanitation, claimed the lives of nineteen settlers in the early months. Despite these hardships, by the end of 1652, the gardens began producing modest harvests, supplemented by foraging for wild sorrel and watercress, allowing the station to resupply passing ships and achieve a degree of self-sufficiency.

Interactions with the Khoikhoi People

The Dutch encountered three distinct Khoikhoi clans in the Cape area. The Goringhaikona (also known as Watermans or Strandlopers), a small group of 50–60 people without cattle, subsisted primarily on fishing, shellfish, seals, and roots, living a more coastal foraging lifestyle. They were led by Autshumato (known to the Dutch as Herry or Harry), a key intermediary in early interactions. The pastoral Goringhaiqua (often called Kaapmans or Saldanhars), under chief Gogosoa, were significantly larger, with substantial herds of cattle and sheep. The Gorachouqua, led by Choro, maintained smaller herds.

The pastoral Khoikhoi led a semi-nomadic lifestyle, centred on herding large numbers of long-horned cattle and fat-tailed sheep. These animals provided milk (a dietary staple), meat, hides for clothing and karosses (blankets), and served as important symbols of wealth and status. To sustain their herds, clans practised transhumance, moving seasonally in search of fresh grazing and water—often spending summers near coastal areas and migrating inland during winter. Their tools were primarily of stone and bone, supplemented by a few metal items acquired through earlier contacts with European ships.

Barter with the Dutch commenced almost immediately upon their arrival, focusing on acquiring Khoikhoi cattle and sheep in exchange for metal goods, glass beads, tobacco pipes, and small quantities of brandy or arrack—items valued by the Khoikhoi for their novelty and utility in crafting ornaments and weapons. The settlers needed fresh meat to combat malnutrition and hides for leather goods, while the Khoikhoi gained durable imports that supplemented their traditional tools.

Autshumato emerged as a central figure in these exchanges. He had prior experience with Europeans, having spent time aboard an English ship where he learned basic English from sailors, and travelled to Bantam (Java) aboard the same vessel—where he acquired some Dutch vocabulary and observed company operations. He facilitated trade negotiations with various Khoikhoi groups, proved to be a skilled negotiator, and advised his people on negotiation tactics.

.

Boer History

Boer History