1657: The Free Burghers "Boers"

Historical Context and Establishment

The establishment of the free burghers at the Cape of Good Hope in 1657 represented a significant development in the early history of Dutch settlement in southern Africa. This initiative by the Dutch East India Company (VOC) aimed to address the limitations of company-managed agriculture and to promote a more sustainable provisioning system for ships en route to the East Indies. The Cape station, founded in 1652 under Commander Jan van Riebeeck, had initially relied on company servants for farming and livestock management, but these efforts proved inefficient due to high costs, labor shortages, and inconsistent yields. By 1655, the VOC directors in the Netherlands had begun considering the release of servants to cultivate land independently, drawing on precedents from settlements in India where freemen had contributed to local economies without undermining company control.

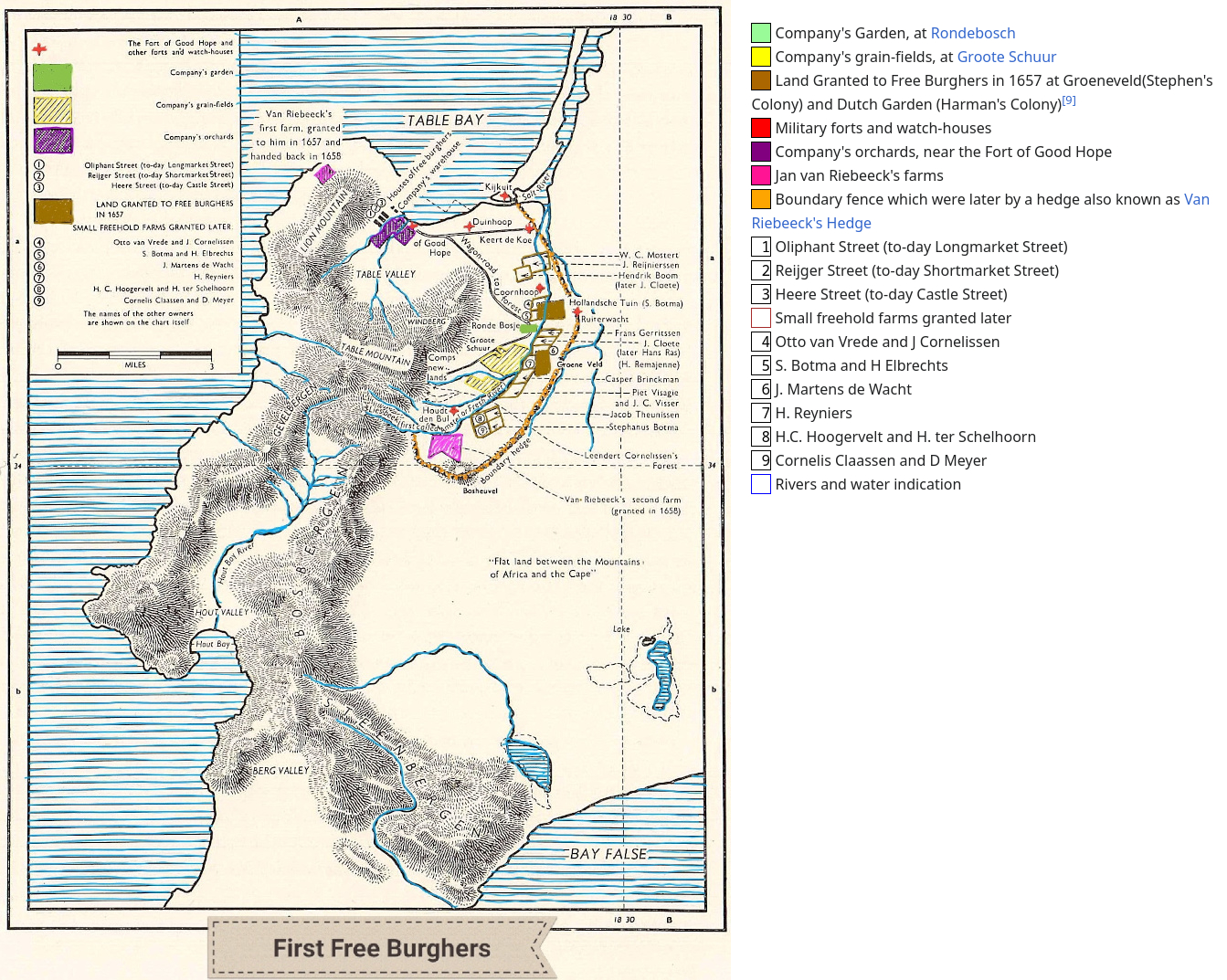

The formal establishment of the free burghers occurred on 21 February 1657, when nine former VOC servants were granted discharges and allocated arable land along the Liesbeeck River, a watercourse originating from the eastern slopes of Table Mountain and flowing northward into Table Bay via its confluence with the Salt River. The river, named after a minor stream in the Netherlands and alternatively spelled Liesbeek, spanned approximately nine kilometers in length, with its banks offering fertile alluvial soils suitable for cultivation amid the otherwise arid and rocky terrain of the Cape Peninsula. The selection of this location was deliberate, as it provided access to fresh water for irrigation, proximity to the fort for defense, and separation from the company's primary gardens to avoid direct competition. The Liesbeeck's course wound through areas that would later become known as Bishopscourt, Newlands, Rondebosch, Rosebank, Mowbray, and Observatory, with its lower reaches characterized by barren, rocky soils and sparse vegetation, while upstream sections benefited from mountain runoff.

Location and Layout of Settlements

The land layout was divided into two distinct colonies to accommodate different agricultural focuses and group compositions. The first, known as Harman's Colony or Groene Veld (Green Field), was positioned on the far eastern bank of the Liesbeeck, approximately fifteen kilometers from the Fort de Goede Hoop—though some contemporary accounts suggest distances closer to three miles (about five kilometers) for the initial plots, with extensions reaching further into the flats behind Table Mountain, up to nineteen kilometers in total for exploratory markings conducted on 19-20 February 1657. This positioning placed it opposite the company's grain fields at Groote Schuur and adjacent to natural boundaries like the river itself, which served as a demarcation line. The terrain here featured gently sloping valleys conducive to wheat farming, with the river providing a natural barrier against potential incursions from indigenous groups and facilitating transport of goods via small boats or overland paths.

In contrast, Steven's Colony, also called Hollandsche Tuin (Dutch Garden), occupied the near western bank, nearer to the fort at Rondebosch, roughly three to five kilometers distant, allowing for easier oversight and quicker response in case of threats. This site's layout included plots extending along the river's edge, with access to the company's orchards and fortifications nearby. The overall configuration formed a linear settlement pattern hugging the riverbanks, with plots oriented perpendicular to the water to maximize irrigation potential. Distances between the two colonies were minimal, separated only by the Liesbeeck's width—typically twenty to thirty meters in the mid-sections—enabling mutual support among the settlers. From the fort in Table Bay, the route to these lands followed established paths skirting Table Mountain's base, traversing about five kilometers to Rondebosch and an additional ten kilometers to the more remote sections of Groene Veld. Historical maps from the period, such as those preserved in Dutch archives, depict this arrangement with notations for company's gardens, grain fields, small freehold farms, boundary fences (later formalized as Van Riebeeck's Hedge), and military outposts like Duynhoop and Coornhoop, which were erected to guard the perimeters.

Application and Selection Process

The process by which these free burghers obtained their land involved a formal application system, reflecting the VOC's cautious approach to delegation. Potential candidates, drawn exclusively from company ranks—predominantly Dutch and German Protestants with maritime or military backgrounds—submitted requests for discharge to the Cape Council. By September 1657, twenty such applications had been received, but only the most reliable were approved, based on criteria including demonstrated agricultural aptitude, marital status (all nine initial grantees were married, ensuring family commitment to permanence), and a pledge to reside at the Cape for at least twenty years. The selection emphasized individuals unlikely to abandon the settlement, with Van Riebeeck personally vetting applicants to exclude those deemed unreliable or prone to conflict with indigenous peoples. For instance, the first group under Harman Remajenne included men with varied skills: Jan Maartensz de Wacht, a marine from Vreeland; Jan van Passel, a soldier from Geel; Warnar Cornelissen, a boatman from Nunspeet; and Roelof Janssen, a soldier from Dalen. The second group, led by Steven Jansz Botma, a sailor from Wageningen, comprised Hendrik Elbrechts, a cadet from Ossenbrugge; Otto Janssen, a soldier from Vreede; and Jacob Cornelissen, a soldier from Rosendaal.

Applicants were required to appear before the authorities, where they received letters of freedom outlining their new status. The land allocation permitted them to select plots "as long and broad as they wished," though this was soon standardized to approximately thirteen to fifteen morgen (eleven to eleven-and-a-half hectares) per individual to prevent overextension and ensure manageability. A morgen, the traditional Dutch unit of land measurement equivalent to about 0.85 hectares, was deemed sufficient for family-scale farming. The grants were in perpetual freehold, meaning inheritable ownership without reversion to the company, but subject to initial exemptions and ongoing obligations.

Roles and Occupations of Free Burghers

The early free burghers were mostly petty officers with families, who drew money instead of rations, and who could derive a portion of their food from their gardens, as well as sell their vegetables to the Company and passing ships to obtain an income. The opportunities to become a successful entrepreneur were abundant and many skilled Europeans applied for free burgher status. The VOC had built a corn mill which was operated by the use of horses, but after a short time it was decided to make use of river water as a motive power. The tender for the construction of the mill was awarded to free burgher Wouter Mostert and when it was in working order he took charge of it and received income on shares of payments made for grinding.

Some of the men who had received land established themselves as farmers while others took service with the farmers as farm workers. Leendert Cornelissen, a ships carpenter, received a grant of a strip of forest at the foot of the mountain. His object was to cut timber for sale, all kinds of which prices were fixed by the council while Elbert Dirksen and Hendrik van Surwerden made a living as tailors. Most received their free papers because they possessed a certain useful skill such as Christian Janssen and Peter Cornelissen who had been expert hunters in the Company's service. Most free burghers negotiated deals with the VOC which were beneficial to both the Company and the burgher such as Dr Jan Vetteman, the surgeon of the fort, who arranged for a monopoly of practice in his profession.

The free burghers nominated persons among them who could serve as representatives at the Council meetings at the Cape. The first burgher Councilor (Dutch title: burgherraden), Steven Jansz, was appointed in 1657 by Rijcklof van Goens. The following year he was joined by his colleague Hendrik Boom to serve as burgherraden in the Council.

Economic Conditions and Restrictions

The terms of the deal struck a balance between autonomy and VOC control, encapsulating the colonial economic model. Each burgher received tax exemption for twelve years, after which moderate levies would apply, calculated as a tenth of produce or livestock. Tools, seeds, and initial livestock were provided on credit from company stores, repayable through deductions from harvests sold back to the VOC. Pricing was fixed: the company committed to purchasing oxen or cows at twenty-five gulden each and sheep at three gulden, while reserving a tenth of all bred animals as payment for grazing rights on communal lands. Marketing restrictions were stringent; burghers could sell to passing ships only after a three-day priority period for the company, ensuring the fort's supplies remained paramount. Independent trade in cattle with the Khoikhoi was prohibited to avoid competition, with all such transactions routed through the VOC at predetermined rates—burghers could barter only with company-supplied goods like brass and tobacco. Excessive cultivation of tobacco was curtailed to prioritize staple grains, and any commerce infringing on the VOC's monopoly in spices or other Eastern goods was forbidden.

The conditions attached to their status were designed to balance individual incentives with company interests. Each burgher received approximately 13.5 morgen (about 11 hectares) of arable land in full property, tax-free for twelve years, after which a reasonable assessment would apply. They were provided with agricultural implements, seed, and cattle on credit from the company magazine, repayable through produce. Sales of vegetables and livestock were restricted: burghers could sell to passing ships only after three days of arrival, and all cattle trades with indigenous groups were prohibited to prevent competition with the company. In exchange, the company guaranteed purchases at fixed prices—25 gulden per ox or cow and 3 gulden per sheep—while claiming one-tenth of reared cattle as payment for pasturage. Burghers were obligated to remain at the Cape for twenty years, swear oaths of allegiance to the States General, the Prince of Orange, and the VOC, and participate in militia duties, including guarding redoubts such as Duynhoop and Coornhoop. They were prohibited from growing tobacco in excess or engaging in private trade that might undermine the company's monopoly.

Boer History

Boer History