1652: Castle of Good Hope

Establishment of the First Fort

The Dutch East India Company, formally known as the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, faced persistent challenges in maintaining its maritime trade routes to the East Indies, with scurvy claiming numerous lives among crews during the protracted voyages. To mitigate this, the directors, or Lords Seventeen, dispatched Jan van Riebeeck with explicit instructions to establish a refreshment station at the Cape of Good Hope, where ships could replenish supplies of fresh water, produce, and meat. The expedition, comprising the ships Drommedaris (as flagship), Reijger, and Goede Hoop, departed Texel on December 24, 1651, and arrived in Table Bay on April 6, 1652, carrying 181 men excluding officers, along with tools, seeds, and livestock. Van Riebeeck's mandate emphasized the construction of a fort to provide security in the unfamiliar region, including for potential interactions with local Khoikhoi herders or rival European powers, while prioritizing agricultural development to ensure self-sufficiency. On April 8, 1652, van Riebeeck formally took possession of the "Kaapse Uithoek" in the name of the V.O.C. and the High Mighty States-General. The selected site in Table Valley, near the Fresh River (now beneath modern Cape Town's Grand Parade and main Post Office, approximately where the old railway station and O.K. Bazaar once stood), offered natural advantages with its sheltered harbor, abundant water from Table Mountain streams, and proximity to fertile ground, though initial surveys revealed variable soil quality and exposure to fierce southeast winds. [1]

Construction and Use of Fort de Goede Hoop

Construction of the quadrangular Fort de Goede Hoop began immediately after landing on April 7, with a square design featuring bastions at each corner, walls 252 Rhynland feet long per face, 20 feet thick at the base tapering to 16 feet at the top, and 12 feet high, topped by a parapet and surrounded by a moat fed by the river. Materials included earth and clay for the walls, timber for internal structures like dwellings and storehouses, and sod to face the earthworks against erosion. Challenges abounded: weakened laborers from the voyage, harsh south-easter winds blinding workers with dust, hard ground for quarrying, and winter rains causing floods that washed away early gardens twice, implying risks of wall collapses. By May 7, bastions were named after ships; the fort was defensively viable by August 1652, with alterations like palisades added by 1653, and inner structures completed in 1656. It served primarily as a defensive stronghold with four iron culverins per bastion, a base for agricultural experiments planting vegetables like cabbages and onions, a kraal for pastured cattle obtained through trade, and administrative quarters where Van Riebeeck's family resided and the first European child in South Africa was born on June 6. However, its walls proved unsuitable for defending against enemies from the sea or inland, highlighting the need for a more permanent structure. [1]

Reasons for Building the Castle of Good Hope

By the early 1660s, the earthen Fort de Goede Hoop's vulnerabilities had become apparent: its clay walls eroded under incessant rains, rendering it inadequate against artillery or naval bombardment, while its armaments proved ineffective against seaborne threats. Escalating Anglo-Dutch rivalries, fueled by commercial competition in the East, culminated in rumors of war in 1664, with formal hostilities erupting in March 1665 during the Second Anglo-Dutch War. The Lords Seventeen, apprehensive of British seizures of Dutch East India Company possessions, instructed Commander Zacharias Wagenaer in 1664 to erect a more resilient stone fortress, modeled on pentagonal bastion designs prevalent in European and Asian fortifications, to safeguard the Cape's strategic value as a midpoint refreshment post. Commissioner Isbrand Goske, arriving in February 1665, inspected potential sites and selected one 60 Rhynland roods (about 225 meters) east of the old fort, despite excavations revealing unexpectedly deep sand requiring foundations up to 11 feet or more for stability. The design centered on a reliable water well beneath the "Boog" arch, ensuring self-sufficiency during sieges. Engineer Pieter Dombaer directed the project, and on January 2, 1666, a ceremonial laying of the cornerstones occurred, performed by Wagenaer, clergyman Johan van Arckel, secunde Abraham Gabbema, and fiscal Hendrik Lacus, amid recitations of poetry, feasts, and disbursements of brandy and tobacco to laborers, symbolizing the Dutch East India Company's commitment to fortifying its imperial outpost. [1]

Construction of the Castle

The construction process drew upon diverse resources: local Table Mountain stone was quarried, shells from Robben Island burned into lime for mortar fortified with sand and shell fragments, timber felled from Hout Bay forests, and decorative clinker bricks ("Ijsel-stene") imported as ship ballast from the Netherlands. A workforce of approximately 300 comprised sailors and soldiers from transient fleets, company servants, free burghers, local Khoikhoi hired for manual tasks, women contributing to shell collection, convicts, and enslaved individuals from West Africa and Asia, with farmers compensated at 6s 3d per day for wagon, oxen, and driver services. The work adhered to the principles of the Old Dutch fortification system, as applied in the Dutch Republic and its overseas settlements from the early 17th century. Foundations, 1 meter wide and 3 to 6 meters deep on rock, were laid after clearing and leveling the ground. Assisted by carpenter Adriaan van Braeckel and master stonemason Douwe Gerbrandtz Steyn, progress was halting: the first bastion, Leerdam, reached completion on November 5, 1670, but the Treaty of Breda in 1667 halted work in May, leaving four bastions scarcely begun after 21 months; renewal came in 1672 under commander Albert van Breugel and commissioner Aernout van Overbeke amid the Third Anglo-Dutch War, accelerating efforts. By the winter of 1674, the structure was sufficiently robust for the garrison's relocation and the old fort's demolition; full completion was achieved on April 26, 1679, during Johan Bax van Herenthals' tenure (1676-1678), with acting commander Hendrik Crudop overseeing the closing phases. Funding constraints from the parsimonious Dutch East India Company, prioritizing profits over infrastructure, contributed to the protracted timeline, yet the result was a formidable pentagon capable of withstanding prolonged assaults. [1]

Design, Features, and Early Uses

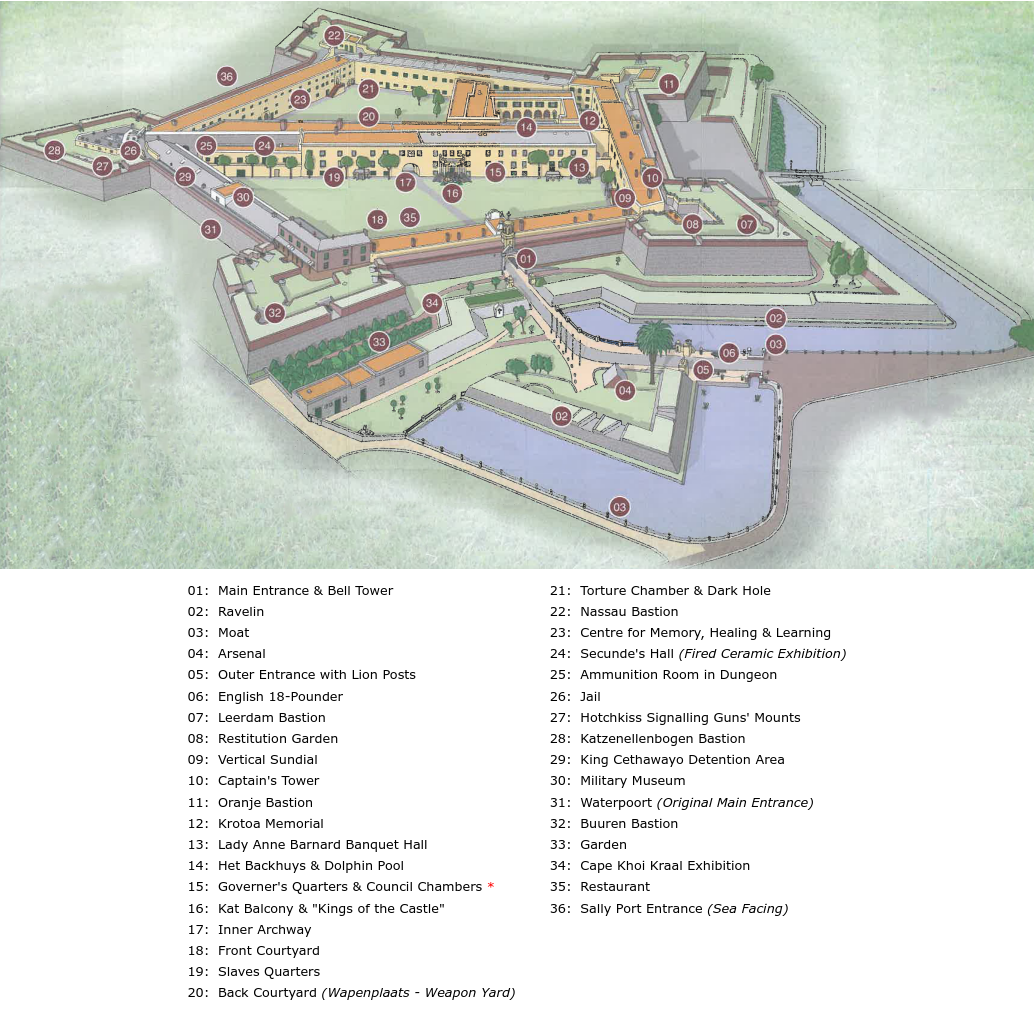

The Castle, so named for its resemblance to European citadels combining defense with communal self-containment, incorporated five bastions titled after Prince William III of Orange-Nassau: Leerdam (west, with the paymaster's office and kitchens), Buuren (north, with officer and troop barracks mounting 12-, 18-, and 24-pounder cannons, a garden where Lady Anne Barnard walked in 1797-1798, and a toll gate for inland products), Catzenellenbogen (east, site of the Donker Gat prison and other cells where the old Dutch Tricolor flag flew), Nassau (southeast, with warehouses and offices), and Oranje (south, housing armor keepers, gunsmith residences, and workshops). Walls rose 10 meters on the seaward side and higher landward to facilitate cross-fire, with the pentagonal layout enabling overlapping cannonades from 48 emplacements (totaling around 100 cannons in the 18th century), rendering approaches impenetrable; each wall (courtine) between bastions was 150 meters long, with right-angled bastion flanks for mutual coverage, and a powder magazine under each bastion. A 25-meter-wide moat, initiated on November 26, 1677, and supplied by Table Mountain springs, enhanced defenses but later deteriorated due to stagnant water and refuse; defensive additions included ravelin fortifications (couvrefaces) outside the walls up to Devil's Peak, and coastal forts to address vulnerabilities if enemies occupied the peak. An original exit gate with iron doors was between Nassau and Catzenellenbogen, but the entrance shifted in 1683 by Simon van der Stel to the curtain between Buuren and Leerdam (current location), featuring a clock tower built of "klompies" stones, with a 1697 Amsterdam-cast bell. The entrance crown displayed the coat of arms of the United Netherlands, V.O.C. monogram, and shields of Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Delft, Zeeland, Hoorn, and Enkhuizen. Internally, it housed a church, bakery, workshops, residences, offices, and cells, serving as the Cape's administrative nexus from 1679. The governor's office, "De Kat," hosted the Council of Policy and Justice from 1674, regulating colonial affairs from residency permits to commodity prices; the transect wall, "Het Oude Kat," contained a chapel interring figures like Krotoa (Eva), the Khoikhoi interpreter; "Het Nieuwe Kat" quartered the governor and secunde atop wine cellars. The De Kat Balcony, erected in 1695 as "De Puij" and reconstructed in 1786-1790 by architect Louis Thibault, facilitated public proclamations, judicial sentences, and receptions, with features like grooved kiaat pillars, wrought iron work, balustrades with yellow copper knobs, balcony decorations, and wood carvings by sculptor Anton Anreith (whose workshop was at the junction of the cross-wall and outer wall between Leerdam and Oranje). Timekeeping relied on sundials—eastern for mornings, western for afternoons—and a 1684 bell tower with a 1697 Amsterdam-forged bell tolling hours, alarms, and signals, supplemented by hourglasses for night watches. Yellow paint on walls minimized glare and heat, while the Captain's Tower between Leerdam and Oranje afforded panoramic surveillance. Early under governors like Isbrand Goske (1672-1676), it functioned as the "frontier fortress of India," mounting heavy ordnance and garrisoning troops, with no major sieges materializing; pyramid stacks of cannonballs were in inner yards for emergencies, and the Castle had its own water well (still standing). [1]

Role Under Later Commanders and in Colonial Society

Simon van der Stel, succeeding on October 12, 1679, and governing until June 1, 1691, elevated the Castle's stature, utilizing it as a base for exploratory forays into the interior for copper and livestock, while fostering viticulture and agriculture that bolstered the colony's economy; he also built grain cellars adjacent to the second-in-command's residence and ordered the entrance shift. His son, Willem Adriaan van der Stel (1699-1707), continued expansions but faced burgher discontent leading to his recall. Subsequent commanders, such as Louis van Assenburgh (1708-1711) and Mauritius Pasques de Chavonnes (1714-1721), oversaw administrative routines, with the Castle hosting church services for a burgeoning congregation, courts dispensing justice—including executions on its grounds—and social events blending European customs with local adaptations. Interactions with Khoikhoi and San peoples evolved from barter to conflict over resources, with the Castle providing refuge during skirmishes like the 1673-1677 Khoikhoi-Dutch wars. In the 18th century, French influences appeared in architectural flourishes, while British modifications post-1806 introduced pitched roofs and brickwork. The garrison jail, designed by Thibault in 1786, featured cells for inebriated soldiers and up to 20 prisoners, with apertures for food delivery. Commissioner Van Rheede van Oudtshoorn ordered the 12-meter-high Kat wall, crossing the interior to the midpoint between Leerdam and Oranje, with a gate (bearing the old sundial) connecting the outer yard (holding government offices and the leather army captain's residence) to the inner yard (wapenplaats); the governor's residence, completed in 1695 with a large council chamber (used as a church until 1704, later a reception hall for Lady Anne Barnard), was a focal point. Throughout the Dutch era, the Castle anchored the nascent Boer society, embodying settler tenacity amid isolation, merging military vigilance with civilian governance. From 1674 to 1795, it served as the headquarters of the Dutch East India Company's government at the Cape and the official residence of the governor; in the first half of the 19th century, British governors used it similarly, after which it remained the army headquarters and seat of government services until departments shifted in the 19th century. [1]

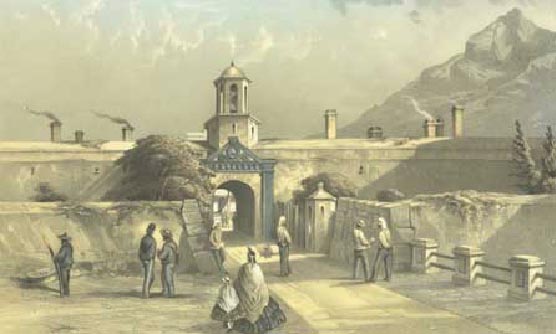

Transition to Modern Heritage Site

The Castle's role shifted dramatically with the British occupation in September 1795, when Governor Abraham Josias Sluysken surrendered it to Admiral George Keith Elphinstone's forces without resistance; it served as British headquarters until the 1803 Peace of Amiens returned the Cape to Batavian rule. Reoccupied by the British in January 1806 following the Battle of Blaauwberg, it became a key military installation, housing governors like Lord Charles Somerset (1814-1826) and witnessing administrative reforms. During the frontier wars, it functioned as a command center and prison, notably detaining Boer prisoners during the Second Boer War (1899-1902). Architectural alterations included British stonework in the 1830s and filling the moat in 1896 for railway expansion. In 1917, the Imperial Forces handed it to the South African Army, which continues to use it. Proclaimed a heritage site in 1936 as the oldest and most historically significant building in South Africa, its 20th-century evolution included quartering troops during World War I, aiding coastal defenses and hosting ceremonies in World War II, and symbolizing colonial legacy amid post-1948 debates under apartheid. Comprehensive restorations commenced in 1982 (completed 1993) and 2014-2016 preserved its fabric, positioning it for UNESCO consideration. Today, as South Africa's oldest extant structure (1666-1679), it accommodates the William Fehr Collection (acquired 1952, illustrating VOC to Victorian eras), the FIRED ceramic exhibit, and the Castle Military Museum. [1]

Boer History

Boer History