The Post 1994 and 30 Years later

In 1994, South Africa launched one of the most ambitious social experiments in modern history: the forging of a “Rainbow Nation.” Under Nelson Mandela and the ANC, the country abandoned the structured recognition of ethnic and cultural differences that had defined governance for decades and instead imposed a single, centralized, multicultural democracy. The promise was reconciliation, equality, and prosperity for all within one indivisible nation. The reality has been a steady unraveling that the architects of the previous order had explicitly warned against: deep-seated cultural incompatibilities cannot be legislated away.

This shift was endorsed by white South Africans in the 1992 apartheid referendum, a whites-only vote held on March 17, 1992. The question posed was whether to support the continuation of reforms initiated by President F.W. de Klerk, aimed at negotiating a new constitution to end apartheid. With a high turnout of around 85-86%, 68.7% voted "yes" (1,924,186 votes) and 31.3% "no" (875,619 votes), signaling a majority desire for change and equality. Many white voters, hopeful for a peaceful transition and true reconciliation, were unaware of the severe challenges that would follow under ANC governance, including economic decline, rampant crime, discrimination and systemic corruption that have eroded the nation's stability.

Violent Farm Murders

A critical element in the post-1994 rural security collapse was the ANC government's decision to dismantle the commando system. Established from the 1770s and refined over centuries, these part-time units—largely composed of local Boer farmers under the South African Defence Force—provided effective patrols, rapid response, and protection across isolated farmlands where regular police presence was minimal. The system maintained low rural crime levels and enabled safe, productive farming communities.

In 2003, President Thabo Mbeki announced the progressive phase-out, completed by 2008. The ANC presented this as eliminating apartheid-era structures associated with alleged abuses and incompatible with democratic principles. Farm organizations such as TAU SA and AfriForum condemned the move as politically motivated. Some analysts and critics theorize that the closure was intended to covertly weaken Boer farming communities, facilitating attacks that would pressure land redistribution and advance expropriation goals by removing the primary local defense mechanism. The promised SAPS replacements—enhanced sector policing, reservists, and patrols—failed to materialize adequately, leaving a dangerous vacuum. These attacks stand apart from ordinary crime due to extreme brutality: prolonged torture, burning, mutilation, and executions, often with little or no theft. Premeditation—scouting farms and exploiting isolation—combined with low conviction rates (under 5% in many periods) and ties to land grievances fuels perceptions of targeted intimidation aimed at reclaiming land.

Race-Based Laws: Justifying Reverse Discrimination

Since South Africa's transition to democracy in 1994, the ANC-led government has enacted or perpetuated a system of race-based laws—currently around 145 operative ones, according to the latest updates to the South African Institute of Race Relations (IRR)'s Index of Race Law (as of mid-2025, with totals revised to 324 race laws ever adopted since 1910). These are frequently justified under official euphemisms such as "redress the imbalances of the past", "redress the results of past racial discriminatory laws or practices", "advance economic transformation", "enhance the economic participation of black people", "achieve equitable representation", and "implement affirmative action measures to redress the disadvantages in employment experienced by designated groups" (as stated in the preambles and objectives of key acts like the Employment Equity Act 55 of 1998, the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Act 53 of 2003, and the Expropriation Act 13 of 2024).

These policies are presented as positive, restorative actions to promote "equal opportunity and fair treatment", eliminate "unfair discrimination", and ensure "suitably qualified people from designated groups have equal employment opportunities" while pursuing "broad-based black economic empowerment" as a framework for "inclusive economic growth" and "social transformation". Government statements defend them as constitutional imperatives under sections like 9(2) (equality clause allowing measures to advance disadvantaged groups), 25 (property clause permitting expropriation for public interest tied to land reform and redress), and 195 (public administration requiring broad representation to redress past imbalances), rejecting opposition as "anti-transformation", attempts to "preserve historical inequalities", or "sabotaging transformation goals" (e.g., recent ministerial and ANC responses to legal challenges).

However, a closer examination reveals these justifications enable a system of reverse discrimination that systematically disadvantages the white population (and other non-designated groups) in employment, business ownership, public procurement, land access, and beyond. The "redress" and "transformation" rhetoric masks mandatory racial classifications and preferences that prioritize "black" Bantu individuals and entities to meet demographic targets or scoring criteria, often at the expense of merit and equal treatment—framed as temporary but persisting indefinitely without clear metrics for success.

Parliament has adopted at least 122 novel or standalone racial statutes since 1994 (with some pre-1994 acts retrospectively racialized through post-1994 amendments), contributing to the current 145 operative race laws. This exceeds the apartheid-era peak of 123 operative race laws in 1980 and means the democratic era accounts for a substantial portion of all racial legislation in South African history since 1910.

The Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (B-BBEE) Act of 2003, which mandates racial preferences in ownership, management control, skills development, and preferential procurement to "advance economic transformation and enhance the economic participation of black people". This is framed as "broadening the economic base" and "deracialising business ownership". In reality, it sidelines white-owned businesses from government contracts and opportunities unless they meet black ownership/management thresholds, often forcing divestment or partnerships that transfer control, with non-compliance leading to exclusion, fines (up to R1.5 million in some cases), or loss of licenses.

The Expropriation Act of 2024 (effective 2025), which allows for "nil compensation" in expropriations deemed "just and equitable" for "public interest", including land reform to "redress the results of past racial discriminatory laws or practices". Officially, this facilitates "equitable access to natural resources" in limited cases (e.g., speculative or unused land). In practice, it enables state seizure without payment, as seen in emerging test cases like Ekurhuleni's 2025 effort, where ANC officials argue no compensation is needed for "land acquired through apartheid systems"—critics call this confiscation under a redress guise, risking broader property rights erosion.

The Employment Equity Act of 1998 (as amended), which requires designated employers to implement "affirmative action measures" and set numerical targets for "equitable representation" aligned with demographic profiles of the economically active population. Officially, this promotes "a diverse workforce broadly representative of our people" and "redress the disadvantages in employment experienced by designated groups". In practice, it functions as racial quotas that bar or severely limit white candidates in many sectors to achieve compliance, with penalties for failure and justifications for non-compliance limited to "reasonable grounds."

Realisation of the failed globalist experiment. "Rainbow Nation"

Pre-1994, South Africa faced overwhelming international pressure—from Western mostly leftist liberals, progressive governments, global institutions like the UN, and crippling sanctions—to abandon its previous system and embrace a "Rainbow Nation." Vastly different ethnic and cultural groups were crammed into a single centralized democracy, banking on the idealistic notion that deep-seated differences could be dissolved through legislation and goodwill into harmonious unity.

Put simply, Khoi, Zulu, Xhosa, and other cultures simply do not want to assimilate into Boer (Afrikaner) culture—and Boers do not want to assimilate into Khoi, Zulu, Xhosa, or other groups. We are just too culturally different, those that say they can are lying to themselves, with distinct languages, traditions, values, and ways of life that clash rather than blend.

Human societies thrive on shared values, trust, and cohesion. Thirty years later, the results are stark: unemployment remains stubbornly high at around 32%, one of the world's highest murder rates, rampant corruption crippling municipalities and institutions, economic stagnation with sluggish growth, crumbling infrastructure like power and water, and deepening inequality.

In stark contrast, the Afrikaner community of Orania thrives with near-zero crime (no need for a police force, violent incidents extremely rare), zero unemployment (everyone works, no joblessness), and manages its own municipality services perfectly—including reliable power through solar energy independence, consistent water supply, and efficient sewage and other infrastructure—while the rest of the country's municipalities fail under mismanagement and load-shedding. The melting pot has boiled over into resentment, violence, and division, proving that such imposed unity, when forced without regard for cultural realities, often erodes social fabric rather than strengthening it. True harmony requires recognizing boundaries, not pretending they don't exist.

The way forward

To secure the long-term survival and strength of our Boer identity—our language, traditions, values, and resilient way of life—in the face of a society that is increasingly fragmented and indifferent to our heritage, we must act with deliberate focus. Spreading thinly across large areas only dilutes our collective influence and makes preservation harder. Instead, we should concentrate our efforts in strategically viable regions with natural resources, economic potential, and historical ties: the productive coastal and inland areas from Kleinmond through to George in the Western Cape, combined with the established model of Orania in the Northern Cape. These locations provide the practical foundation for building cohesive, self-sustaining communities where our culture can be actively maintained and strengthened through shared purpose and mutual support.

A core element of this strategy is intentional demographic growth. In an environment of demographic challenges and cultural pressures, prioritizing larger families is a direct and effective way to build the numbers needed for sustainability. More children ensure the continuous transmission of Afrikaans, our customs, and our worldview to future generations, while providing the human capital to support community expansion, economic activity, and long-term defense of our spaces. By settling in these targeted zones and committing to family growth as a calculated priority, we create the demographic momentum required to secure and scale these enclaves effectively.

The path to establishing secure, thriving Afrikaner communities is clear and achievable: Purchase houses, plots, and farms in towns and coastal areas within the designated zones. From the outset, prioritize self-sufficiency—install solar power systems for independent energy; implement water purification, boreholes, and rainwater harvesting; develop food production through gardens, orchards, livestock, and efficient farming techniques. Form organized communities with shared governance, education, and businesses aligned around common goals. As numbers grow and internal cohesion strengthens, the natural next step is to engage more actively with the structures already in place at the local level. In smaller towns and rural municipalities—where voter turnout is often modest and community voices carry further—individuals and aligned residents can step forward as candidates in upcoming local elections. These contests, represent a realistic opportunity to increase representation on town councils. When sufficient influence is gained through steady, legitimate participation, it becomes possible to guide municipal decisions in directions that better serve the long-term interests of the residents who built and sustain the area: prioritizing practical infrastructure improvements, reliable service delivery that matches real community needs, and careful stewardship of local resources to support ongoing development from within.

In the meantime, while that level of sway is still being built, concentrate effort and support exclusively on strengthening the parallel community systems already under way—keeping external municipal dependencies to the practical minimum required by law. Wherever feasible, continue handling core services through internal organization and private means: efficient waste management via recycling and composting programs, reliable operation of water supply and sanitation arrangements, expansion of independent power generation capacity, and routine upkeep of local roads and access ways using pooled community resources and voluntary labor. Throughout, remain fully compliant with all national legal requirements while applying every available legitimate method to keep tax liabilities as low as possible—through careful use of allowable deductions, thoughtful structuring of property and business ownership, and deliberate focus of expenditure on internal priorities.

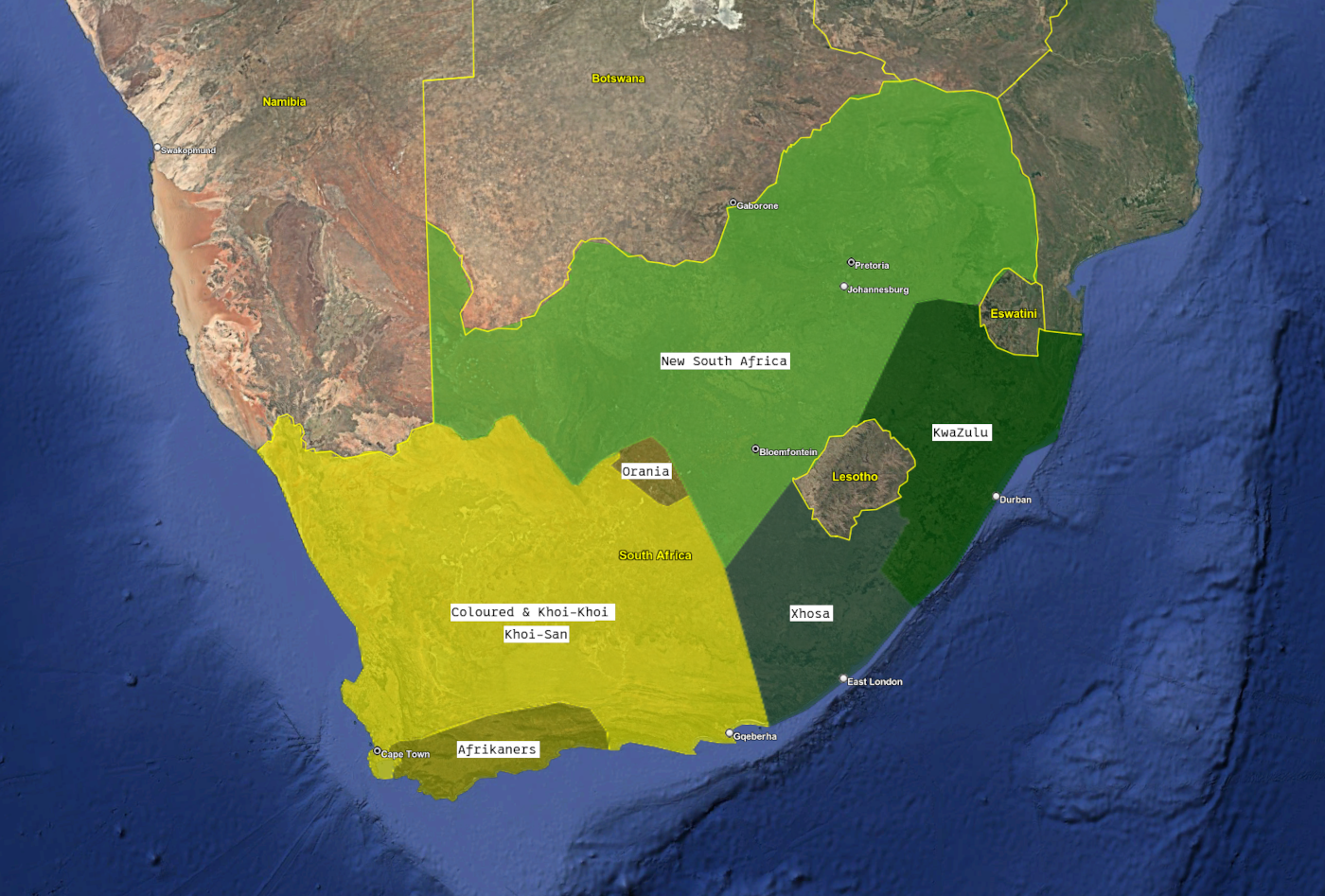

The attached map clearly divides South Africa along historical and cultural lines, reflecting natural ethnic territories rather than forced unity.

Boer History

Boer History