The First Khoikhoi-Dutch War (1659–1660)

In 1659, the Cape settlement experienced its first significant armed conflict between the Dutch East India Company (VOC) settlers led by Commander Jan van Riebeeck and specific indigenous Khoikhoi clans of the region, namely the Goringhaiqua and Gorachouqua. This was not a conventional war but a series of cattle raids, retaliatory actions, and defensive measures that stemmed from fundamental differences in how the two groups understood and used land. [1]

Causes of the Conflict

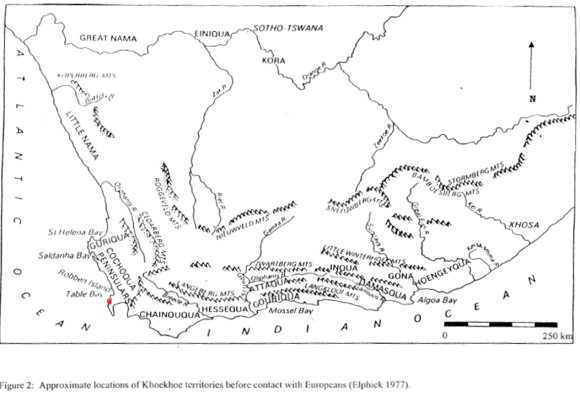

the desputed area marked in red estimate size 1 km²

The Khoikhoi were semi-nomadic pastoralists who migrated seasonally with their cattle and sheep herds to access grazing and water sources. They saw land as a communal resource, not something that could be privately owned, fenced, or permanently settled. European ships (Portuguese, English, and Dutch) had visited the Cape for over a century before 1652, trading briefly for livestock and water without major conflict, as the visitors departed quickly. The VOC's establishment of a permanent refreshment station in 1652 changed this. [1]

From 1657 onward, land along the Liesbeeck River and nearby areas was granted in freehold to free burghers (former VOC employees). These farms were enclosed, cultivated for crops like wheat and vegetables, and occupied long-term. When the Goringhaiqua and Gorachouqua clans—primarily under leaders such as Gogosoa (referred to as the "fat captain" for the Goringhaiqua)—returned to traditional summer pastures near Table Mountain in early 1659, they found grazing routes blocked by houses, fields, and hedges. Water points were restricted, and stray cattle straying onto farms sparked disputes. A key resistance leader was Doman (also called Nommoa or "simple face"), a member of the Goringhaiqua who had worked at the fort, learned Dutch, and was sent to Batavia. Initially viewed as loyal, he became disillusioned after seeing VOC treatment of indigenous peoples in the East Indies and resolved to resist permanent Dutch settlement. Under his influence, the Goringhaiqua and Gorachouqua launched opportunistic night raids and attacks during rainy weather (when Dutch matchlock muskets often failed due to damp powder), targeting isolated burgher herds. [1]

Escalation

The conflict escalated with the killing of free burgher Simon Janssen, who was herding cattle and was attacked and killed with assegais (spear) by a group led by Doman. This incident caused outrage and fear among the settlers. The vryburghers regrouped at the fort. Burghers, many of whom had prior experience as Company officers, demanded the right to protect their property. On 19 May 1659 the Council of Policy, after consulting burgher representatives Hendrik Boom and Jan Reyniers, authorised defensive and retaliatory steps. While the VOC directors' instructions prohibited unnecessary violence against natives, the council permitted the seizure of Khoikhoi cattle as hostages as to pressure an end to the raids. [1]

Dutch Defenses

The Goringhaiqua and Gorachouqua avoided open fights, preferring to use their speed and knowledge of the land to strike quickly and disappear. Dutch patrols and expeditions, such as those led by Corporal Elias Giers or guided by the interpreter Harry (a former beachranger recalled from Robben Island), seldom managed to catch the moving Khoikhoi encampments. [1]

The Dutch tried to win over rival Khoikhoi groups that were not involved in the raids, especially the Cochoquas under their chief Oedasoa. Oedasoa's people lived farther north and east, often around the Berg River area, and were more powerful than the Peninsula clans. The Dutch hoped these rivals could put pressure on the Goringhaiqua and Gorachouqua, provide information, or even help in some way against them. Eva (Krotoa), the young Khoikhoi woman who lived in Van Riebeeck's household and spoke Dutch fluently, was sent as interpreter because she was connected to Oedasoa—her sister was one of his wives. The Dutch made several deputations to Oedasoa's encampment, bringing gifts like tobacco, bread, rice, and brandy. They held talks with Oedasoa and his council of elders. Oedasoa spoke against the Peninsula clans' actions, called them troublemakers, and said the Dutch should deal with them firmly. He and his people made promises to help, but nothing concrete ever came of it—no warriors, no guides, no real support. In the end, the Cochoquas stayed neutral. [1]

To protect the settlement, the Dutch deepened the Liesbeeck River crossings, built watch-houses at key spots (including Keert de Koe, Houdt den Bul, and Kijkuijt), and planted a thorn hedge—later known as Van Riebeeck's Hedge—to mark an early boundary. Mounted patrols kept watch, and passing ships brought extra soldiers, horses, and dogs, giving the Dutch a strong advantage. In one clash, Fiscal Abraham Gabbema and three horsemen killed three attackers and wounded two, including Doman, who escaped. Corporal Giers led another action that scattered beachrangers, killing three and wounding several. By late 1659, many inland groups had moved toward Saldanha Bay, easing the immediate threat. Both sides were worn out—the Goringhaiqua and Gorachouqua by lost cattle and broken herding patterns, the Dutch by disrupted farming—and they began looking for a way to end the raids before they flared up again with the next season. [1]

Peace and Negotiations

In early 1660, the Peninsula clans reached out through coastal traders, asking for safe passage to the fort. Harry and Doman, seeing the value of written agreements over spoken ones, urged a formal treaty. On 6 April 1660, Gogosoa, Harry, Doman, and about forty followers met Van Riebeeck, secunde Roelof de Man, and fiscal Abraham Gabbema. After talks, they agreed on terms: no more attacks and past wrongs forgotten; the Khoikhoi to use set paths for trade and replace stolen livestock; the Dutch to keep the land and roads they held; and wrongdoers punished by their own people. Van Riebeeck made it clear the settled areas would be defended by force if needed. To seal the deal, they gave 10 cows and nine sheep, and received generous gifts back. [1]

Boer History

Boer History